05-01-3. Beyond the Edge: The Craft of Wabocho Making

we explored the rich history of Japanese knives and how their diverse types have supported Japanese food culture. However, the true charm of Japanese knives lies not only in their functionality and historical background. Their soul resides deep within the blade itself, and in the hands and hearts of the craftsmen who create them.

In this chapter, we delve deeply into the manufacturing process that gives Japanese knives their unparalleled sharpness and beautiful appearance. From the selection of steel, to the traditional techniques of forging steel in the flames, and the precise process of hand-sharpening each blade, we will uncover the “Takumi” craftsmanship behind Japanese knife making. Through this journey, you will gain a deep understanding of why the Japanese knife you hold in your hands is not merely a tool, but a work of art imbued with the soul of the craftsman.

3.1 The Heart of Steel: Understanding Japanese Carbon & Stainless Steel

The sharpness and durability of Japanese knives depend on the type of steel used. Japanese knife craftsmen have long refined their skills in selecting and processing the most suitable steel for each type of knife. Today, Japanese knives are mainly made from two types of steel: carbon steel and stainless steel. Understanding the characteristics of each type of steel is essential to understanding the true value of Japanese knives.

Carbon Steel: The King of Sharpness

Many traditional Japanese knives are made of high-carbon steel. This material has been used since the days of Japanese sword smiths, and its characteristics embody the philosophy of Japanese knives, which is the pursuit of sharpness.

Properties and Advantages

- Unparalleled Sharpness: Carbon steel is extremely hard and can produce an extremely sharp cutting edge. This allows it to slice through food fibers smoothly, as if “sucking” them in, without crushing them. This feature is particularly useful when cutting delicate sashimi.

- Ease of Sharpening: Despite its high hardness, carbon steel responds well to sharpening stones and is relatively easy to sharpen. For skilled craftsmen and chefs, this ease of sharpening is a crucial factor in maintaining the highest level of sharpness. Each time you sharpen it, you can feel the knife come back to life.

- Edge Retention: Carbon steel knives that have been properly heat-treated maintain their sharpness for a relatively long time after sharpening. This does not mean that frequent sharpening is unnecessary, but rather that the “peak sharpness” after sharpening lasts longer.

- The Beauty of Patina: Carbon steel develops a unique bluish or blackish oxide film called “kuro-sabi” (patina) on its surface as it is used. Unlike red rust, this patina serves to protect the knife and creates a unique “character” and “style” that can only be achieved through extensive use. This patina is one of the reasons many chefs choose carbon steel knives and serves as a testament to the fact that knives are “living tools.”

Key Types of Carbon Steel

- Shirogami-ko (White Steel): This is a type of carbon steel with few impurities and a very high purity. It is easy to sharpen and produces a very sharp cutting edge. It is particularly popular among skilled craftsmen and chefs, but it is characterized by its high susceptibility to rust. There are several types, including “Shirogami No. 1,” “Shirogami No. 2,” and “Shirogami No. 3.” No. 1 is the hardest and has the best cutting performance, but it requires more maintenance.

- Blue Steel (Aogami-ko): A carbon steel alloyed with elements such as chromium and tungsten to enhance toughness (resilience) and wear resistance (edge retention). While it is not as easy to sharpen as Shirogami steel, it is harder and has better edge retention, making it suitable for professional use. There are various types, such as “Aogami No. 1,” “Aogami No. 2,” and “Aogami Super,” with Aogami Super being particularly high-performance and highly regarded among professionals.

Drawbacks and Importance of Maintenance

- Susceptibility to Rust: The biggest drawback of carbon steel is that it is prone to rusting when exposed to moisture or acid. Therefore, thorough maintenance is essential: after use, wash immediately, thoroughly dry, and store in a dry location. Even the slightest neglect in maintenance can lead to rusting, which damages both sharpness and appearance. This maintenance effort is also considered part of the joy of “cultivating” a carbon steel knife.

Stainless Steel: Fusion of Convenience and Evolution

After World War II, stainless steel began to gain popularity, and due to its rust resistance, it became widely used as a material for knives. Initially, it was considered inferior to carbon steel in terms of sharpness and durability, but with advances in technology, modern stainless steel Japanese knives have undergone remarkable improvements.

- Properties and Advantages:

- Corrosion Resistance: The most significant advantage is its high chromium content, which makes it highly resistant to rust. This makes maintenance much easier and has led to its widespread use in households. It can be used with relative peace of mind even in humid environments.

- Ease of Maintenance: Unlike carbon steel, it does not require strict maintenance, making it ideal for everyday use.

- Diverse Alloys: In recent years, high-performance stainless steels (e.g., VG10, AUS-10, powdered high-speed steel, etc.) have been developed by adding alloy elements such as cobalt, molybdenum, and vanadium, achieving cutting performance and edge retention that rival or even surpass those of carbon steel.

- Drawbacks:

- Difficulty in Sharpening: While it is harder than carbon steel, its toughness can make sharpening challenging for some users. Sharpening may take longer or feel more difficult.

- Initial Sharpness: Except for high-performance stainless steels, general-purpose stainless steels may not match the “sharpness” of newly sharpened carbon steel.

Clad Steel: Best of Both Worlds

Many modern Japanese knives are made of a composite material called “Fukugo-zai,” which combines the best features of carbon steel and stainless steel. This material consists of a core material (blade steel) that provides sharpness, sandwiched between a rust-resistant and durable outer material (base metal).

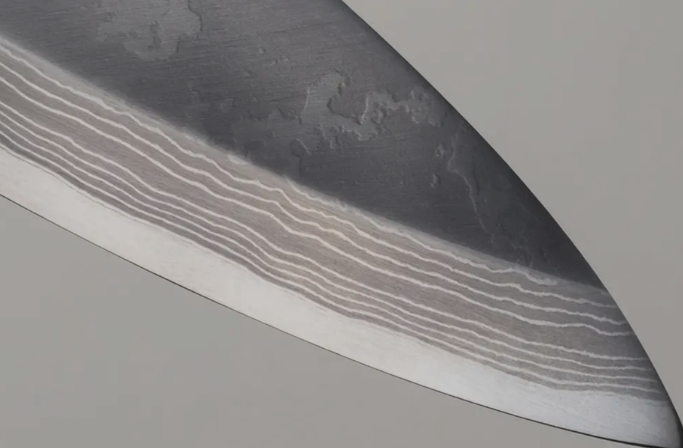

- Damascus Steel: One of the most representative composite materials is Damascus steel, which is characterized by its beautiful ripples and woodgrain-like patterns. These patterns are created by forging layers of different metals, and in addition to their aesthetic appeal, they also enhance the strength and flexibility of the blade.

Choosing the Right Steel for You

When choosing a Japanese knife, the type of steel you select will depend on how often you cook, your willingness to maintain the knife, and the sharpness you desire.

- If you seek the sharpest edge and the joy of maintenance: Carbon steel

- If you prioritize ease of maintenance and convenience for daily use: Stainless steel

- If you seek a balance between sharpness and maintenance, along with beauty: Composite materials(Damascus steel)

The blade of a Japanese knife takes on entirely different characteristics depending on the type of steel used. By understanding this “heart of the steel,” you will find knife selection more enjoyable and your daily cooking will become even more fulfilling.

3.2 Forged in Fire: The Traditional Art of Hand-Hammering & Heat Treatment

The exceptional quality of Japanese knives cannot be achieved simply by selecting superior steel. Its essence lies in the traditional forging techniques of fire and hammer, known as “Tanzo,” and the subsequent “heat treatment (Netsu-shori).” This is an extremely delicate process that requires the long-standing experience and intuition of craftsmen, passed down from the days of sword smiths.

Forging: Imbuing Steel with Soul

Forging is a process in which steel is heated to a high temperature and shaped by hammering. This process has a deeper meaning than simply creating a shape.

- 1. Hi-zukuri – Heating and Shaping

- First, the craftsman heats the steel in a high-temperature furnace until it turns red. The temperature at this stage is strictly adjusted according to the type of steel and the desired quality.

- The heated steel is then repeatedly struck with a hammer. This “striking” process is extremely important. By striking the steel, its internal crystalline structure becomes denser, impurities are expelled, and its strength and toughness (ductility) are significantly enhanced. Much like kneading dough, the molecules of the steel rearrange themselves, transforming it into a more uniform and resilient material.

- In particular, the “Awase-tanzo” technique, which involves layering and hammering different types of steel together, creates the ideal characteristics of a Japanese knife: “durability and sustained sharpness.” This is achieved by sandwiching hard, sharp steel (blade steel) between flexible, durable soft iron (base steel). The Damascus pattern is also formed during this process.

- 2. Hi-narashi – Normalizing

- After forging, the steel is reheated to the appropriate temperature and slowly cooled to remove internal stress and stabilize the structure. This process maximizes the effectiveness of subsequent heat treatment.

This forging process is not merely a physical task. The craftsman communicates with the steel through its color, sound, vibration, and tactile feedback, striving to unlock its full potential. It is, in essence, the act of infusing the steel with a “soul.”

Heat Treatment: The Deciding Factor for Sharpness

Forged steel undergoes a critical process called “heat treatment” to achieve its ultimate sharpness and durability. This is a fusion of science and art that optimizes the hardness and toughness of steel.

- 1. Yaki-ire – Quenching:

- The blade is heated to an extremely high temperature (typically around 800°C), then rapidly cooled by immersing it in a cooling liquid such as water or oil. This rapid cooling causes a change in the internal structure of the steel, resulting in the formation of a very hard structure called “martensite.” This gives the knife its remarkable hardness and sharpness.

- However, steel that is too hard becomes brittle and prone to breaking. Therefore, the quenching temperature and cooling speed are strictly controlled based on the type of steel and the desired characteristics of the knife. The key to success lies in the craftsman’s years of experience and precise temperature control.

- 2. Yaki-modoshi – Tempering:

- Knives that have been hardened by heat treatment are extremely brittle in their current state, so they undergo a process called “tempering,” in which they are reheated at a relatively low temperature (typically 150°C to 250°C) and then slowly cooled. This process adds **toughness (ductility)** to the overly hard steel, transforming it into a knife that is less likely to break or chip.

- The temperature and duration of tempering are also critically important in determining the final characteristics of the knife. If the temperature is too high, hardness is lost; if too low, brittleness remains. Craftsmen strive to achieve this delicate balance to maximize the steel’s inherent properties.

This forging and heat treatment process is the most important factor in determining the quality of a Japanese knife. The ability to “read the fire,” which only skilled craftsmen possess—that is, the ability to accurately judge the state of the steel from the color of the flame, the luster of the steel, and the bubbles in the cooling liquid—is essential for the success of these processes. The “soul” of a Japanese knife’s sharpness is truly forged in this fire and water.

3.3 The Secret to Superior Sharpness: The Meticulous Hand-Sharpening Process

After the foundation for a strong blade is established through forging and heat treatment, the process of “togi” (sharpening) by skilled craftsmen is what breathes life into Japanese knives. The ultimate sharpness of Japanese knives is achieved through this meticulous and artistic sharpening process. Sharpening not only sharpens the blade but also maximizes the knife’s performance and highlights its beauty in the final stage.

Types and Roles of Whetstones

Sharpening Japanese knives requires multiple **whetstones (Toishi)** with different grit sizes. Each whetstone plays a different role in the sharpening process.

- 1. Coarse Grit Whetstone (Ara-toishi):

- Role: Used when the blade is severely damaged, when the shape of the blade needs to be significantly altered, or when creating a sharp blade from scratch. It has the ability to quickly remove material from the steel.

- Characteristics: It has a coarse grain size and produces a large amount of sharpening slurry when used.

- 2. Medium Grit Whetstone (Naka-toishi):

- Role: Most frequently used for restoring everyday sharpness. It removes scratches made by the coarse whetstone, further sharpens the blade tip, and establishes the foundation for sharpness. It is an essential whetstone used daily by professional chefs.

- Features: Has finer grains than a coarse whetstone and produces moderate amounts of sharpening slurry.

- 3. Finishing Whetstone (Shiage-toishi):

- Role: Used in the final stage of sharpening. It removes the fine scratches created by the medium whetstone and sharpens the blade to the utmost smoothness, bringing out the best sharpness and luster. This process creates a sharpness that makes food “slide” through the blade.

- Characteristics: It has an extremely fine grain size, producing a smooth grinding slurry when used. Natural whetstones may also fall into this category.

Hand Sharpening Technique: Craftsman’s Feel and Precision

Hand sharpening Japanese knives requires not only the right amount of force and angle adjustment, but also the **sense developed through years of experience** by skilled craftsmen.

- 1. Whetstone Preparation:

- Before use, soak the whetstone in water until it stops releasing bubbles. This keeps the surface of the whetstone moist at all times, enabling efficient sharpening.

- When sharpening, place the whetstone on a dedicated stand or non-slip surface to keep it stable.

- 2. Maintaining the Angle:

- The most important aspect of sharpening Japanese knives is maintaining a consistent angle of the blade. For single-edged Japanese knives (yanagiba, deba, and usuba), it is common to maintain an angle of about 15 degrees between the blade surface and the whetstone. Maintaining this angle accurately will result in a sharp blade.

- Craftsmen use the sensation in their palms and fingertips, as well as the resistance transmitted from the blade, to accurately perceive and adjust subtle differences in angle.

- 3. Burr Formation and Removal:

- As the blade is sharpened, a tiny metal protrusion forms on the opposite side of the sharpened surface. This is called a “kaeri” (burr). The presence of a kaeri indicates that the blade is being sharpened uniformly across its entire surface.

- As you progress from the coarse whetstone to the medium whetstone and then to the finishing whetstone, you will gradually reduce the size of the burr and eventually remove it completely. In particular, when sharpening single-edged knives, it is important to sharpen the front side to create the burr and then lightly sharpen the back side to remove it, a process known as “ura-togi.” This back sharpening is the key to enhancing the durability of the blade and maintaining its sharpness.

- 4. Sharpening Motion:

- To sharpen the entire blade evenly on the whetstone, sharpen it sequentially from the base to the tip, and then sharpen the entire blade. Sharpen by sliding the blade across the whetstone with a consistent amount of force and rhythm.

- Sharpening slurry (mud) is a mixture of grinding stone particles and steel particles, and it is generally used without rinsing off to aid in the grinding process.

The Ultimate Sharpness Achieved by Sharpening

Through this meticulous hand-sharpening process, the blade of a Japanese knife becomes so sharp that it is invisible to the naked eye, with a sharpness measured in microns.

- Cutting without damaging cells: The ultimate sharpened blade cuts through ingredients without crushing their cells, as if “sliding between cells” rather than “cutting.” This preserves the flavor and moisture of the ingredients, significantly enhancing not only their appearance but also their taste and texture.

- The sensation of “cutting”: When cutting ingredients with a freshly sharpened Japanese knife, you can experience a unique sensation of the blade being drawn into the ingredients, as if it were being absorbed. This is one of the greatest joys for a chef.

Sharpening a Japanese knife is not merely a technical task. It is a meditative act through which the craftsman communicates with the knife and brings out its soul. This sharpening process elevates the Japanese knife from a mere tool to a living work of art.

3.4 Handle with Care: Ergonomics and Aesthetics in Wabocho Design

The appeal of Japanese knives lies not only in their sharpness. The handle is also an important element of Japanese knives, embodying Japanese craftsmanship and aesthetic sensibility. The handle contributes greatly to both the ease of use (ergonomics) and visual beauty (aesthetics) of the knife.

Types and Structure of Handles: Designs that Fit the Hand

There are two main types of Japanese knife handles.

- 1. Wa-handle:

- Features: This is the traditional Japanese knife handle, which is mostly made of wood. The tang (the base of the blade) is inserted into the handle and secured with glue or pins. The cross-section of the handle varies, including octagonal, D-shaped (chestnut-shaped), and round.

- Advantages:

- Natural Fit in Hand: Wooden handles absorb the oils from your hands over time, becoming more comfortable to hold. They have a warm feel and are less tiring to use for extended periods.

- Excellent Balance: Wa-style handles are relatively lightweight, so the center of gravity of the knife tends to be closer to the blade. This allows for smooth cutting using the weight of the blade, which is especially important for single-edged knives used for pulling cuts.

- Ease of Replacement: Traditional Japanese-style handles are designed for easy replacement. This is convenient if the handle becomes damaged or if you wish to switch to a handle made of a different material.

- Traditional Aesthetics: The beauty of the wood grain and the understated yet refined design symbolize Japanese aesthetics.

- 2. Western Handle:

- Features: This type of handle is commonly found on Western knives and is made of stainless steel, synthetic resin, laminated reinforced wood, etc. The tang typically runs through the entire handle and is secured with rivets in a “full tang” structure.

- Advantages:

- Durability: The full tang structure and water-resistant materials make it extremely sturdy and durable.

- Hygiene: Materials like synthetic resin are hygienic and easy to maintain.

- Balance: The handle is relatively heavy, often shifting the knife’s center of gravity toward the handle, providing stability.

Handle Materials: Fusion of Functionality and Aesthetics

he handles of Japanese knives are made from a variety of materials, each with its own unique characteristics and beauty.

- Ho Wood: The most common and traditional material used for Japanese knife handles. It has moderate hardness and elasticity, is resistant to water, and is easy to work with. It has a pleasant texture and becomes more comfortable to use over time.

- Ebony / Rosewood, etc.: These are premium woods used in high-end Japanese knives. They are extremely hard, durable, and feature a beautiful luster and unique grain patterns. They are heavy and can affect the knife’s center of gravity.

- Pakkawood: A material made by impregnating thin wooden sheets with resin, then compressing and hardening them. It is water-resistant, durable, and features a beautiful wood grain pattern. It is also commonly used for Western-style handles.

- Synthetic Resin: Lightweight, hygienic, and highly water-resistant. It offers a wide range of colors and designs and is easy to maintain.

(Ergonomics: Extension of the Chef’s Hand

The design of Japanese knife handles is not merely decorative. It incorporates deep ergonomic considerations to function as if the chef’s hand were an extension of the knife itself.

- Comfortable Grip: The shape of the handle is designed to fit the palm of the hand, reducing fatigue even after prolonged use. Octagonal and D-shaped handles provide a secure grip with good finger placement and slip resistance.

- Optimized Balance: The weight of the blade and handle, as well as how they are attached, determine the overall balance of the knife. Ideal balance allows the knife to naturally stabilize in the hand, enabling smooth operation with minimal effort. This balance is particularly crucial for knives with long, heavy blades, such as Yanagiba knives, as it enables precise slicing.

- Control: Proper balance and grip allow chefs to control the knife more accurately and make precise cuts as intended. This is an essential element in preserving the beauty and quality of ingredients in delicate Japanese cuisine.

Aesthetics: The Dignity of a Tool

The handle of a Japanese knife expresses not only its functionality but also its dignity and aesthetics as a tool.

- The beauty of the material: The warmth, grain, and texture of natural wood, which changes with use, give the knife individuality and character.

- Simplicity and harmony: The overall design of Japanese knives is based on the Japanese aesthetic of subtraction, pursuing simplicity while pursuing functional beauty. The harmony in every detail, such as the line between the handle and the blade and the color contrast, gives the knife a quiet elegance.

- “The fusion of utility and beauty”: The concept of “the fusion of utility and beauty,” common to traditional Japanese crafts, is strongly reflected in Japanese knives. They combine the highest functionality with a beauty that captivates the viewer’s heart.

The handle of a Japanese knife is not merely a part that supports the blade. It serves as an interface between the chef and the knife, embodying the fusion of functionality and aesthetics. Carefully selected and crafted handles become an extension of the chef’s hand, transmitting their skill and passion to the ingredients. When you hold a Japanese knife in your hand, feel the warmth emanating from the handle and the endless possibilities it holds.

Conclusion: The Soul Forged in Every Detail

In this chapter, we delved into the core of the manufacturing process that gives Japanese knives their exceptional sharpness and beauty.

The selection of steel determines the “heart” of the knife, and we came to understand the ultimate sharpness and ease of sharpening pursued by carbon steel, as well as the convenience and potential for evolution offered by stainless steel.

Furthermore, the forging process—shaping the steel in the flames—is not merely a physical task but an artistic act where the craftsman infuses the steel with life. The subsequent heat treatment determines the delicate balance of hardness and toughness, ensuring the durability and sustained sharpness of Japanese knives.

Furthermore, the meticulous hand-sharpening process is the pinnacle of craftsmanship, producing the ultimate sharpness that is the “soul” of Japanese knives. The technique of using multiple whetstones, manipulating the edge, and sharpening the blade tip to the micron level enables chefs to bring out the most beautiful aspects of ingredients.

Finally, the ergonomics and aesthetics incorporated into the handle design demonstrate that Japanese knives are not merely tools, but function as an extension of the chef’s hand, combining elegance and functional beauty.

The manufacturing process of Japanese knives embodies the Japanese philosophy of “the fusion of utility and beauty.” Each Japanese knife is imbued with a deep understanding of materials, traditional techniques passed down from predecessors, and above all, the relentless pursuit and soul of the craftsman.

The next time you hold a Japanese knife, feel the passion of the craftsman, the rich history of Japan, and the soul embedded in every detail beyond its sharp blade. It will transform your culinary experience into a profound cultural journey beyond mere meal preparation.