05-01-1. Wabocho Knives(Japanese Traditional knives): The Art & Soul of Japanese Culinary Craftsmanship

1. The Legacy of the Blade: A Deep Dive into Wabocho History

When you step into Japanese food culture, you will be impressed by its exquisite beauty and deep flavors. However, behind this magic lies something more than just culinary skill. It is the tools that Japanese chefs wield with their souls—the “Wabocho” (Japanese kitchen knife). The Wabocho is not merely a kitchen tool. It is a living testament that encapsulates Japan’s rich history, exceptional craftsmanship, and deep respect for ingredients. In this chapter, we will unravel the grand journey of how the Wabocho evolved into its current form.

1.1 From Samurai Swords to Kitchen Essentials: Wabocho’s Evolution

Surprisingly, the origins of Japanese knives can be traced back to the history of Japanese swords. In the era of the samurai, swords were not merely weapons, but also represented the spirit of their owners. For centuries, sword smiths honed their skills in forging and sharpening steel, creating swords that could be called works of art unparalleled in the world. It was this unrivaled skill that later became the foundation of Japanese knives.

Ancient to Medieval Period: The Dawn of Utensils

The history of knives in Japan dates back to the Stone Age, but the iron culture truly began in the Yayoi period. Ironworking techniques introduced from the continent were used to make agricultural tools and weapons, greatly changing people’s lives. Although simple iron knives for cutting food are thought to have existed during this period, they did not yet have the specialization of today’s “kitchen knives.”

During the Heian period, Japanese culture flourished, and court cuisine and vegetarian cuisine began to develop. Records show that more sophisticated knives for cutting food began to be used around this time, but the term “kitchen knife” was not yet in common use. Rather, most of them were considered to be derivatives of the “sword.”

The prototype of the Japanese kitchen knife became clear in the Kamakura period. During this period, samurai rose to prominence, and the demand for swords skyrocketed. Skilled sword smiths gathered from all over the country, and Japanese sword manufacturing technology underwent rapid development. They combined two different types of steel, hard “hagane” and ductile “jigane,” heated them, hammered them, and folded them to create swords with astonishing sharpness and durability.

This sword-making technology would eventually be applied to the world of cooking. The techniques developed in the process of making swords—namely, the “forging” technique of heating and hammering steel to remove impurities and refine its structure, and the “polishing” technique of sharpening the blade—were also applied to kitchen knives. From this period onward, specialized culinary knives—the precursors to modern Japanese kitchen knives—began to be produced.

Muromachi and Azuchi-Momoyama Periods: Culinary Development and Specialization

With the advent of the Muromachi period, the tea ceremony developed, and with it, kaiseki cuisine became established. Kaiseki cuisine is a type of cuisine designed to enhance the enjoyment of tea, featuring seasonal ingredients prepared in small portions with delicate techniques, and emphasizing visual beauty. Such refined cuisine naturally required sharp, specialized knives. The ability to cut ingredients beautifully without damaging their fibers significantly influenced the quality of the dish.

During the Azuchi-Momoyama period, Western culture was introduced to Japan through trade with the South Seas. This influence extended to culinary culture, bringing dishes like tempura. As new cooking methods emerged, the demand for suitable knives gradually increased. However, at this point, the variety of Japanese knives was still limited, and the specialized division of labor seen today had not yet developed.

Edo Period: The Golden Age and Established Specialization of Wabocho

The Japanese kitchen knife established its diverse shapes and specialization and entered its golden age during the Edo period, which saw over 260 years of peace. This era saw the development of cities and the blossoming of the food culture of the common people. Many dishes that form the foundation of today’s Japanese cuisine, such as sushi, tempura, and soba, were born and developed during this period.

The growth of urban areas and the rise of the dining-out culture increased the demand for chefs, who began seeking tools that would allow them to cook more efficiently and beautifully. In response, knife smiths developed new types of knives specialized for various ingredients and cooking methods.

- The Birth of the Deba Bocho:

- The Deba Bocho was invented out of the need to fillet whole fish. It is designed to cut through hard bones and fillet fish into three pieces.

- The Development of the Yanagiba Bocho:

- With the rise of sashimi culture, the Yanagiba Bocho—a long, sharp knife designed to quickly slice raw fish—gained popularity. It minimizes damage to fish cells and maintains a smooth surface, prioritizing both visual appeal and texture.

- The Refinement of the Usuba Bocho:

- With the development of Kyoto cuisine and kaiseki cuisine, which require delicate handling of vegetables, the Usuba Bocho was created, specializing in precise tasks such as thin slicing and peeling. Its thin blade cuts vegetables without damaging their structure, preserving their natural flavor and aroma.

In this way, during the Edo period, knives with the optimal sharpness and shape for each ingredient were devised, and the idea of “using the right tool for the right job” became reflected in the manufacture of Japanese knives. This is deeply connected to the fundamental idea of Japanese cuisine, which is to bring out the best flavor of the ingredients.

During this period, regions such as Sakai (present-day Sakai City, Osaka Prefecture), Echizen (present-day Fukui Prefecture), and **Sekiguchi (present-day Sekiguchi City, Gifu Prefecture)** flourished as major production centers for knives. These regions developed their own unique forging techniques and distribution networks, supplying high-quality Japanese knives nationwide. In particular, Sakai knives were so highly regarded that the Edo shogunate established a monopoly on their production.

Meiji Period Onwards: Modernization and Fusion of Tradition

With the opening of Japan in the Meiji era, Western culture and technology rapidly flooded into the country. In terms of food culture, the habit of eating beef and pork spread, and Western cuisine began to become popular in households. Along with this, Western-style knives, especially double-edged gyuto and petty knives, began to be manufactured in Japan.

However, the traditional techniques of Japanese knives were not lost. Rather, by incorporating Western technology while applying traditional Japanese forging techniques, higher-quality and more diverse knives were produced. For example, the introduction of rust-resistant stainless steel provided a new option for the production of Japanese knives, which had previously been primarily made of carbon steel. Today, traditional single-edged Japanese knives and more versatile double-edged Japanese knives coexist, with chefs selecting the appropriate knife based on their needs.

Today’s Japanese knives are not merely relics of the past. They are living tools that continue to evolve through the fusion of centuries of craftsmen’s knowledge and experience with modern technology. Each one carries the rich history of Japanese culinary culture and the spirit of craftsmen dedicated to pursuing the highest quality cuisine.

1.2 Why Japanese Knives are Different: Unique Design & Philosophy

Japanese knives differ significantly from Western knives in terms of design, functionality, and manufacturing philosophy. These differences are fundamental to the exceptional sharpness of Japanese knives and the delicacy of Japanese cuisine.

The Aesthetic of Single Bevel: Delicate Cuts and Precise Control

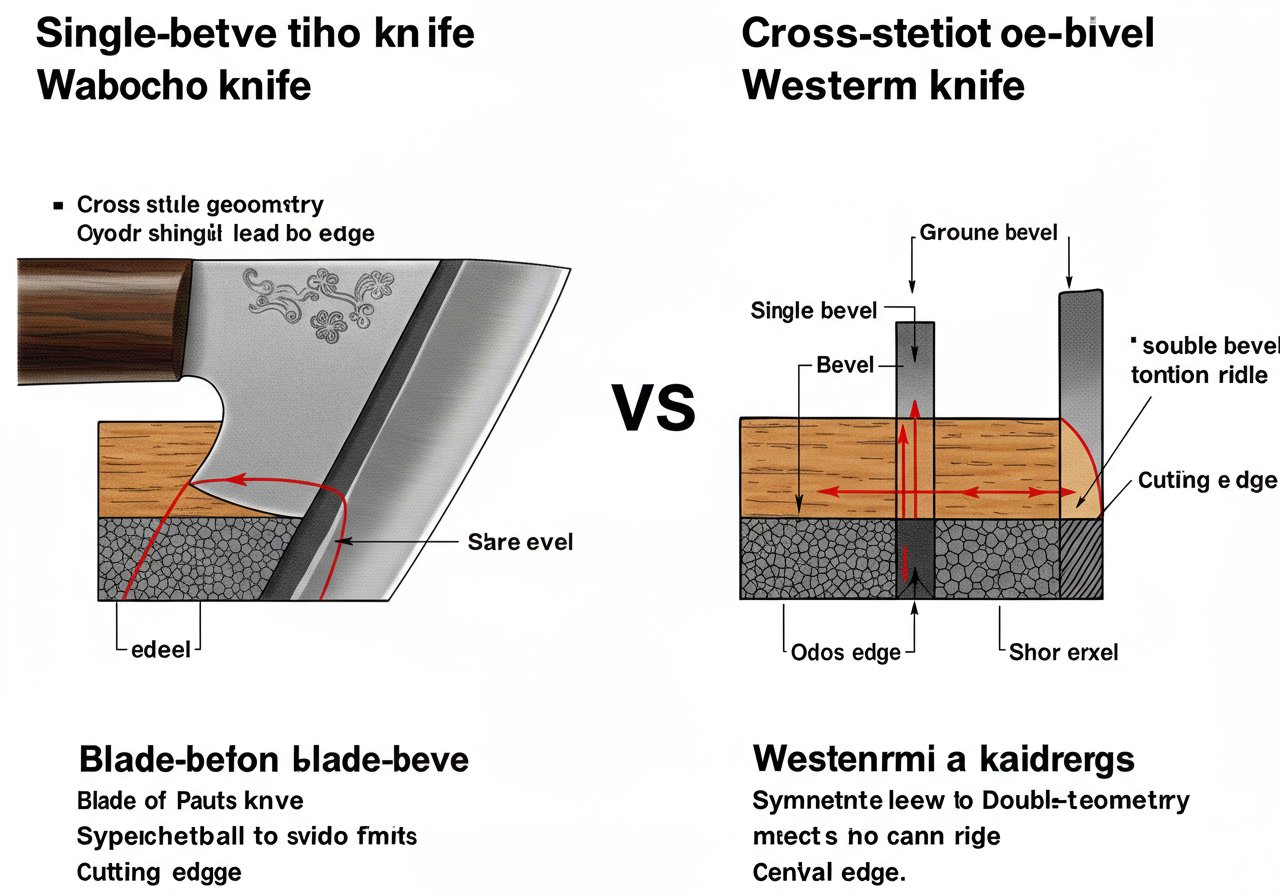

One of the most distinctive differences of Japanese knives is their **”single bevel (Kata-ba)” structure**. While many Western knives are double-edged (Ryo-ba), traditional Japanese knives (such as Yanagi, Deba, and Usuba) have only one side of the blade sharpened. This unique structure provides Japanese knives with their distinctive advantages.

- Ultimate sharpness:

- Single-edged knives are sharpened to a very acute angle, allowing them to cut through ingredients with extremely low resistance. This results in a surprisingly smooth and beautiful cut without destroying the cell walls of the ingredients. For example, when cutting sashimi with a willow-edged knife, you can slice through the fish without damaging its fibers, bringing out its natural flavor and luster to the fullest.

- Precise control:

- Single-edged knives tend to naturally tilt toward the food when cutting. By utilizing this characteristic, chefs can perform thin slicing and decorative cutting with greater precision. Typical examples include peeling with a thin-bladed knife and shredding vegetables.

- Difficulty in sharpening:

- Single-edged knives are considered more difficult to sharpen than double-edged knives. Maintaining the correct angle and performing proper “ura-oshi” (sharpening the back of the blade) requires skilled technique. However, this sharpening process is an essential element in maintaining the sharpness of Japanese knives and is also where the craftsman’s skill truly shines.

Dedication to Steel: The Pursuit of Sharpness and Durability

The superior sharpness of Japanese knives comes from the attention to detail in the steel used to make them. Carrying on the tradition of Japanese sword smiths, Japanese knives are made from a variety of high-quality steels depending on their intended use.

- High Carbon Steel:

- High carbon steels such as “Aogami-ko” and “Shirogami-ko” are extremely hard and provide a very sharp cutting edge. They are easy to sharpen and maintain their edge well, making them popular among professional chefs. However, they are prone to rust, so proper maintenance after use is essential. This tendency to rust also emphasizes the aspect of the knife as a “tool of the soul” that chefs consciously care for and handle with respect.

- Stainless Steel:

- Stainless steel knives, which are rust-resistant and easy to maintain, are also widely used. In recent years, high-performance stainless steels such as powdered high-speed steel have been developed, resulting in Japanese knives that combine carbon steel-like sharpness with rust resistance.

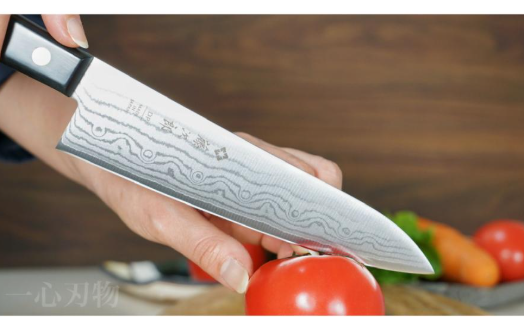

- Composite Materials/Damascus Steel:

- Knives made from composite materials, where a hard high-carbon steel or stainless steel core is sandwiched between softer stainless steel layers, are also common. This design combines the sharpness of the core material with the rust resistance and durability of the outer layers. In particular, the beautiful “Damascus pattern” created by forging multiple layers of different metals is popular as an artistic piece that combines both functionality and aesthetic appeal.

Forging and Heat Treatment: The Soul of the Craftsman

The manufacturing of Japanese knives is not merely a mechanical process. It is an artistic process that tests the years of experience and intuition of skilled craftsmen.

- Forging:

- Forging, which involves heating steel to high temperatures and hammering it to stretch it, is an important process that refines the steel’s structure, removes impurities, and enhances its strength and toughness. Craftsmen carefully assess the state of the steel and rhythmically strike it with a hammer to shape the blade. This manual forging process imparts the knife with its unique toughness and flexibility.

- Quenching and Tempering:

- Quenching, which involves rapidly cooling heated steel to harden it, and tempering, which involves reheating it to an appropriate temperature to impart toughness, are the most critical processes determining the final hardness, sharpness, and durability of a knife. The precise control of temperature and time during this heat treatment process requires the deep knowledge and experience of skilled craftsmen, truly bringing the steel to life.

Handle Attachment and Balance: Tools That Fit the Hand

Another characteristic of Japanese knives is the shape and attachment method of their handles. Many Japanese knives have a structure similar to that of Japanese swords, with the tang (the base of the blade) inserted into a wooden handle and secured in place.

- Materials:

- The handles are made from materials such as magnolia wood, which is water-resistant, durable, and easy to grip, as well as high-quality ebony and **rosewood**. These woods become more comfortable to hold and develop a unique patina over time.

- Center of gravity:

- Many Japanese knives are designed with the center of gravity near the base of the blade. This ensures stability in the hand, reduces fatigue during prolonged use, and enables precise control.

Design Philosophy Embodied by “Wa no Kokoro”

The design of Japanese knives is not only functional, but also deeply reflects the Japanese aesthetic sensibility known as “Wa no Kokoro” (the spirit of harmony).

- The Aesthetics of Subtraction:

- The “aesthetics of subtraction,” which pursues maximum beauty and functionality with the minimum necessary elements, is also evident in Japanese knives. Within their Simple shape with no wasted space, the sharpness of the blade and the beauty of the wood grain on the handle stand out.

- Harmony with Nature:

- Like the philosophy of Japanese cuisine, which emphasizes the use of seasonal ingredients, Japanese knives also prioritize the harmony between natural materials such as steel and wood.

- Ichigo Ichie and Respect for Tools:

- Similar to the spirit of “ichigo ichie” in the tea ceremony, Japanese knives are tools that enable chefs to realize the best possible encounter with ingredients that can only be experienced once. Therefore, chefs treat knives not as mere tools, but as an extension of themselves or spiritual partners. The daily maintenance and sharpening of knives are expressions of deep respect and gratitude for these tools.

The reason Japanese knives are not merely kitchen tools but “works of art” imbued with Japanese culture and spirit lies in the fact that their history, manufacturing techniques, and design philosophy all reflect the unique sensitivity and sincere “do” spirit of the Japanese people. By understanding this profound background, you will feel the soul of the craftsman and the rich story of Japanese food culture every time you hold a Japanese knife.